The transition from the Arabic alphabet to the Latin one, the disconnection from the Ottoman past with the foundation of the Republic, and turning to the West -whilst being located right in the Middle East- have no doubt resulted in casualties, one of which is definitely Ottoman arts and culture. Holding a degree in Western languages and literatures, I impatiently waited for long years to see the Bayeux tapestry, which depicts the Norman invasion of England and the battle of Hastings and it did sweep me off my feet when I finally made it to Normandy to see it with my very eyes on a rainy gloomy day. That’s how we connect to other cultures, of which we are not members; through exposure. However, it took a much longer time to discover and appreciate the beauty of Surname-i Vehbi. I had to un-learn many things before getting my hands on and being consumed by it.

Ottoman Historiography: Surname, the Book of Festivals

Image is a no-no in Islam, or that’s what we were told all along. What we are taught about the Ottomans at school is mostly confined to its military achievements. So no wonder why I was taken aback when I first came across the hard cover print edition of the legendary Ottoman manuscripts with illustrations. Only few copies are known to have survived due to wars during the breakdown of the empire. Today, the manuscripts you get to see displayed at the museums in the West are the ones commissioned by Europeans. The manuscripts –illustrated or not- shed light into how Ottoman history writing shaped the Ottoman identity and culture over the centuries. All the while, you cannot help but wonder what if, what if the religion had put no restrained on the use of images.

Of many different types of manuscripts ranging from technical, scientific, erotic, cosmological, astrological, mystical to dream interpretation topics, only a few were illustrated. Surname-i Vehbi is one of those precious illustrated ones. And this is no ordinary book; this is a Surname, a book of festivals. Sur translates as festival whereas name translates as writing. These state-sponsored festivals conducted and narrated for the purpose of imposing an Ottoman identity along the lines of their ideology covered a wide range of entertainments very much in the same fashion with the European courts. The festival books were commissioned by the Ottoman state, namely the reigning sultan or a member of the royal family on the occasion of circumcision parties of crown princes, royal births and weddings of princesses.

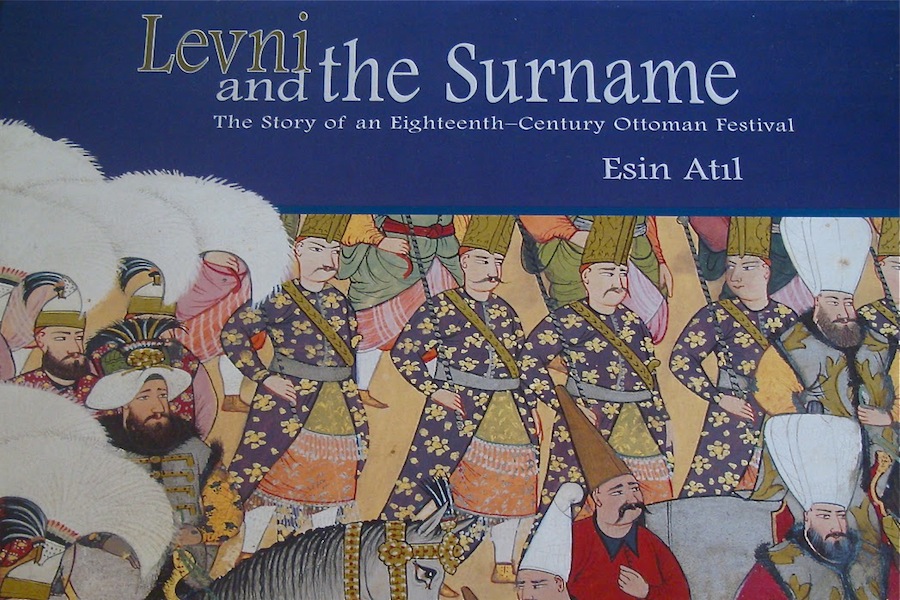

Surname-i Vehbi on the shelves at SALT Galata, one of my favorite research institutes, winked at me this summer. At first, I was hastily and randomly picking details from miniatures and the narrative. With the realization of what I have been holding in my hands, I gave in, dropped the pen and the paper and my smart phone and got totally immersed in this collector’s item browsing through the book first according to the Latin codex, and then according to the Arabic codex, from right to left. Levni’s skillful portraits of Ottoman dignitaries, and all compartments of society at the procession and depiction of the city in different venues, along with the paper quality and the color print were inviting. Nevertheless, if it weren’t for the insight and the context the art historian Dr. Esin Atıl provided, I would not have appreciated enough this book that narrated the story of an 18th century imperial festival.

Vehbi the Poet

Vehbi the poet is the one to narrate the entire program of the last magnificient imperial festival. Remember the square fountain at the entrance gate of Topkapı palace in Sultanahmet? On the inscription lies his 14-line poem in praise of water. Along with Şeyh Galip and Nedim, Vehbi is considered to be one of the master poets of the epoch that marked the second Classical Age of the Ottoman arts and culture, with Sinan’s Age being the first one. It was Persian language that fell out of favor while Turkish words and expressions took hold together with the infusion of local vernacular; a kind of Turkish Renaissance in language and literature appeared.

Levni the Illustrator

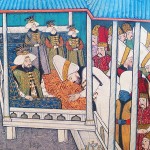

Levni is our nakkaş, the painter, the illustrator/illuminator of this 18th century festival book that celebrated the circumcision of Sultan Ahmed III’s four sons for 55 days. 18th century historian & musicologist Dimitri Cantemir describes him as musavvir– the chief painter, the royal portraist. Levni’s book of portraits of Ottoman rulers, Silsiname and Cantemir’s book, the History of the Growth and Decay of the Ottoman Empire, one of the seminal works on the empire, feature his engravings of all Ottoman sultans until that period. According to another historian, Hafız hüseyin, Abdülcelil Çelebi is his real name and he is originally from Edirne. Levni, his pen name, suits him well for it means colorful, polychromatic, and multi-faceted. This book is considered to be a masterpiece by Levni, a great story teller of his time. Even, this much of a gem enables us to visualize the city in the 18th century. Levni is not the mere illustrator of the text composed by Vehbi, he gives an “eye witness account” as Atıl emphasizes very well. Soft colors and soft brushes are his signature.

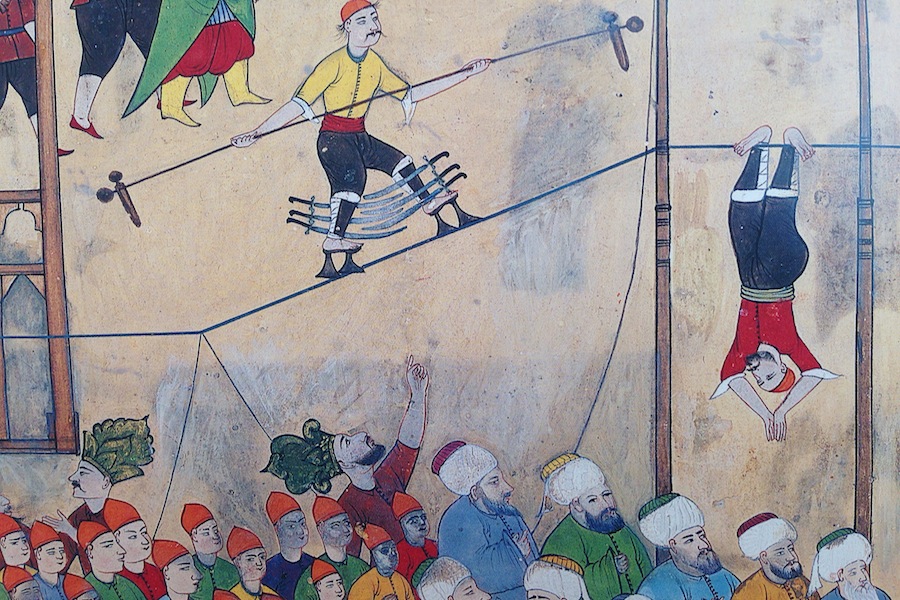

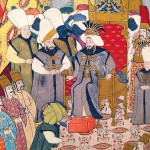

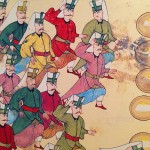

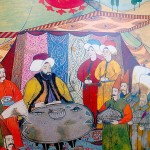

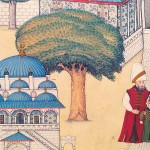

His style and cinematic devices he employs bring the parade alive; figures –spectators and performers of the events- are captured in motion whereas banquets for the dignitaries inspire a sense of stillness and serenity. The parade of each and every guild with their attributes (gifts, goods and wares) reveals a great deal in regards to the organization and production of theses guilds to the modern reader, especially to a visual learner like me. We could well consider it a sociological account of Konstantiniyye and the Tulip period, where the Ottoman state minutely and skillfully portrayed with its administrative, religious and military bodies. The city renders itself visible on both festival grounds –the Golden Horn and Okmeydanı- and at the royal palace, tickling your imagination.

Lale Devri, or the Tulip period (1718-1730)

Tulipmania or the Tulip period is often associated with decadence in Turkish history classes, or to say the least, that’s how the official history prefers to view it. Anything associated with fun, pleasure, and extravagance set the tone for us. Nevertheless, due to economical constraints, the state was actually compelled to construct only small monuments bearing the mark of the period such as small pavillions, square fountains or sebils embellished with floral designs and fruit bowls. These charity works commissioned by devout Muslims were meant to provide water and sherbet for the locals. According to contemporary historian İlber Ortaylı, it was rather an epoch “that heralded momentous changes in civilian architecture, Turkish mansion and neighborhood life and public spaces in urban areas.” The pioneers and patrons of this vibrant cultural and intellectual life were two cultured statesmen: Sultan Ahmed III and his grand vizier Ibrahim Pasha. Politically, it was a relatively stable and peaceful period; the treaties of the 1700s ensured the blossoming of interest and investment in arts and culture. In order to catch up with developments in the West, technical innovations were imported from Europe; military and administrative institutions were modernized in line with their European counterparts. In short, as Esin Atıl pinpoints well, it was “the birth of a modern period despite its shortcomings”.

Click on the arrows to view more photos.

Reference: Levni and the surname, Esin Atil published by Koç Publishing House.

All photos are details from original miniatures; the captions are directly taken from the book. The numbers indicate the page number of the manuscript.

The festival program in a nut shell

0 Beginning of the manuscript with illustrated heading and poetic summary of the festival.

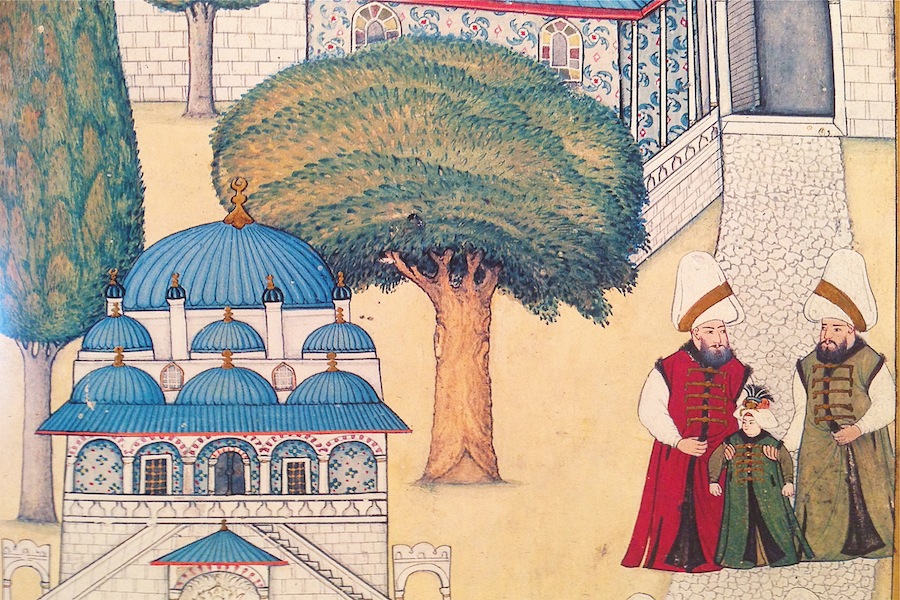

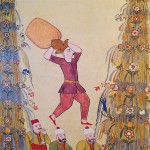

1 Visit to the old palace: 19 days before the festival, the sultan and princes visit the old palace to inspect the candy gardens and nahils -large conical structures embellished with symbolic fruits and flowers. Gate keepers are at the entrance.

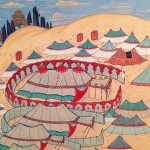

2 View of Ok meydani -the archery grounds: This is the setting for the festival. Imperial closure with canopied tents reserved for men, the largest one being for the grand vizier.

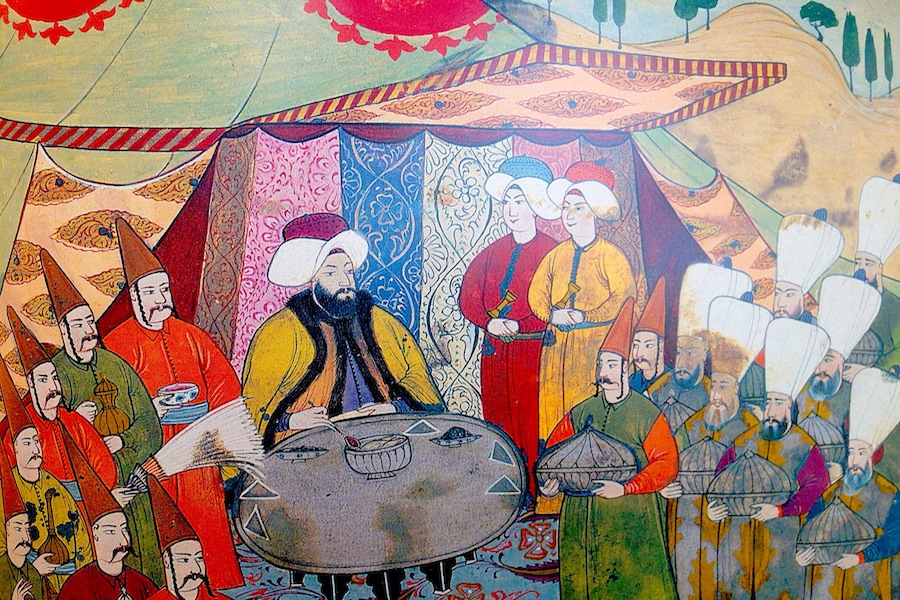

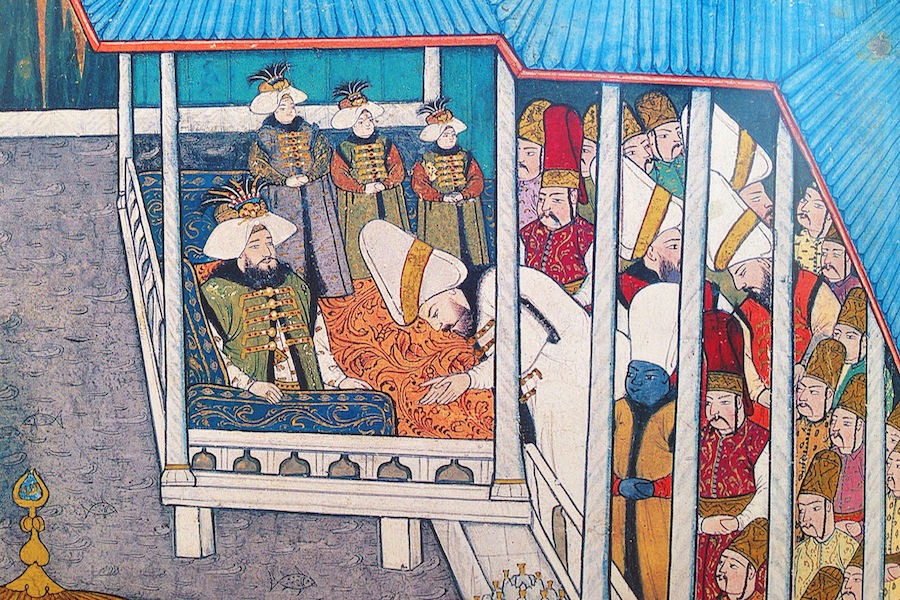

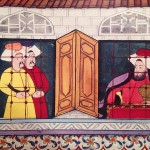

8 Official reception: Sultan Ahmed III enthroned in the canopied tent receiving the dignitaries. Levni’s name is written on one side of the foot stool below the sultan’s feet, which in a way pays homage to his ruler and patron. Festival starts with the official reception.

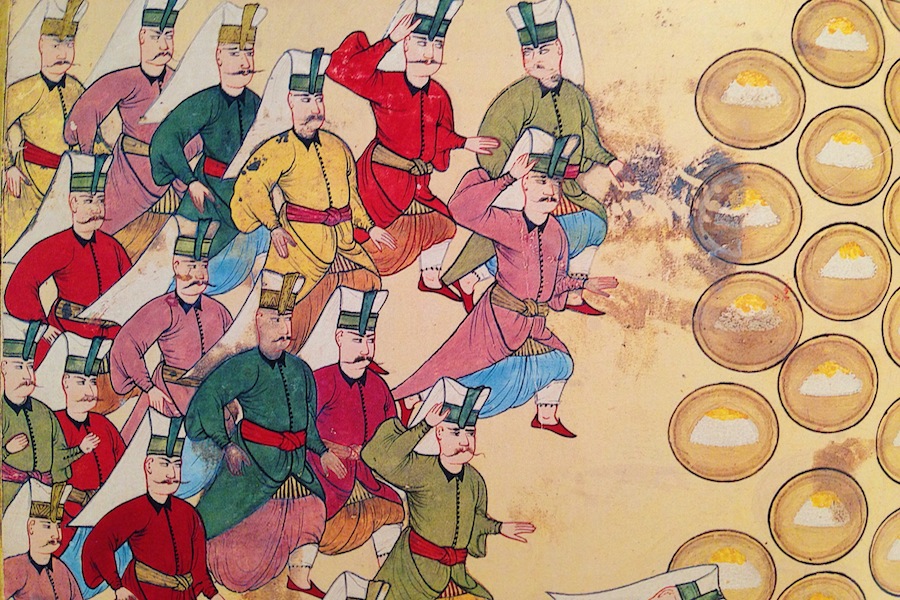

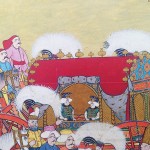

10 Banquet for the Jannisseries: According to the tradition, pilav and zerde -saffran-flavored rice- are served. Jannisseries rush to devour the food.

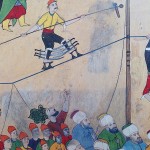

12 Performance of the acrobats: Egyptian acrobats perform on the tight robe.

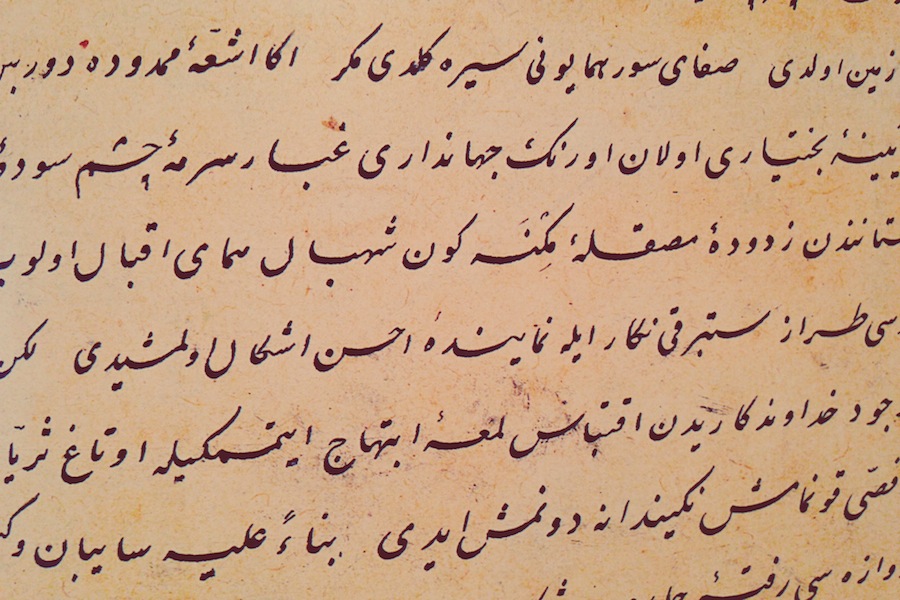

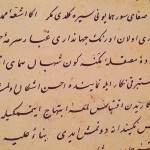

16 Text composed by the poet Vehbi

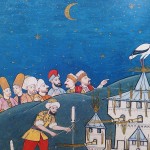

23 Fireworks displays at Ok meydani: The new moon is shining. Fireworks are set off by the Golden Horn, too. Sultan is watching it from Aynalikavak pavillion.

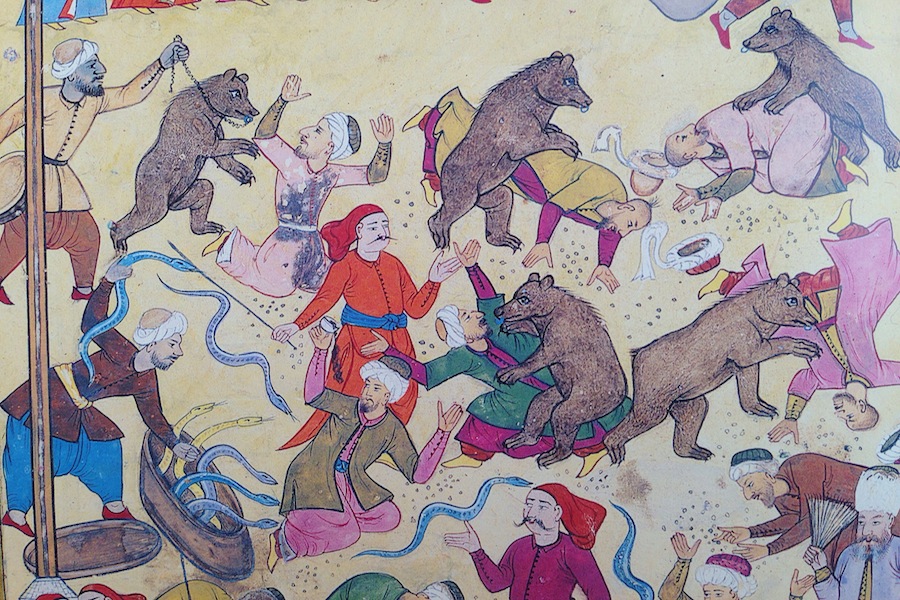

30 Performance of the drug addicts: They are pretending to be intoxicated, puffing their pipes and drinking their coffees and snake charmers. They put an act with trained bears.

34 Procession of guilds: Barbers present their gifts to the sultan in the same fashion the other guilds do. Gifts include silver vessels, embroidered towels and shaving cloths.

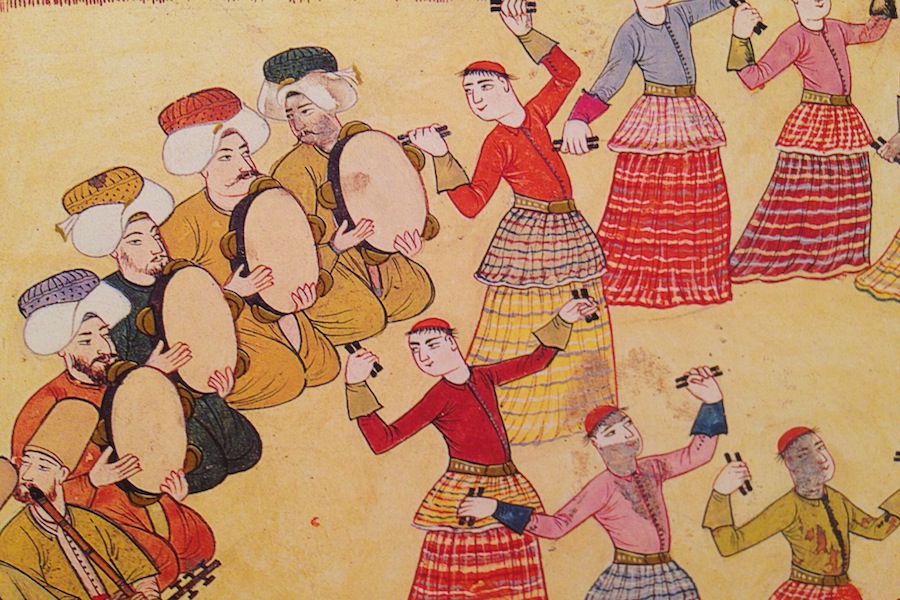

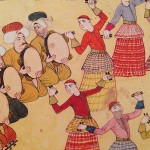

35 Performance of musicians, dancers and acrobats

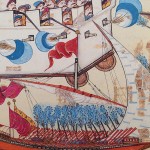

40 Performance of tersane and topcu corps: They are engaged in a mock battle.

47 Banquet for the imperial household: It includes imperial stables, falconers and many others.

48 Fireworks displays on the Golden Horn: They are always accompanied by musical performances. Elaborate shows are performed on rafts floating on the water.

51 The last parade: Among the spectators are foreign ambassadors.

54 Circumcision parade: Gate keepers and surgeons take part in this parade. 150 surgeons are assigned to circumcise 500 boys from poor families as a gesture of charity. Gate keepers accompany them.

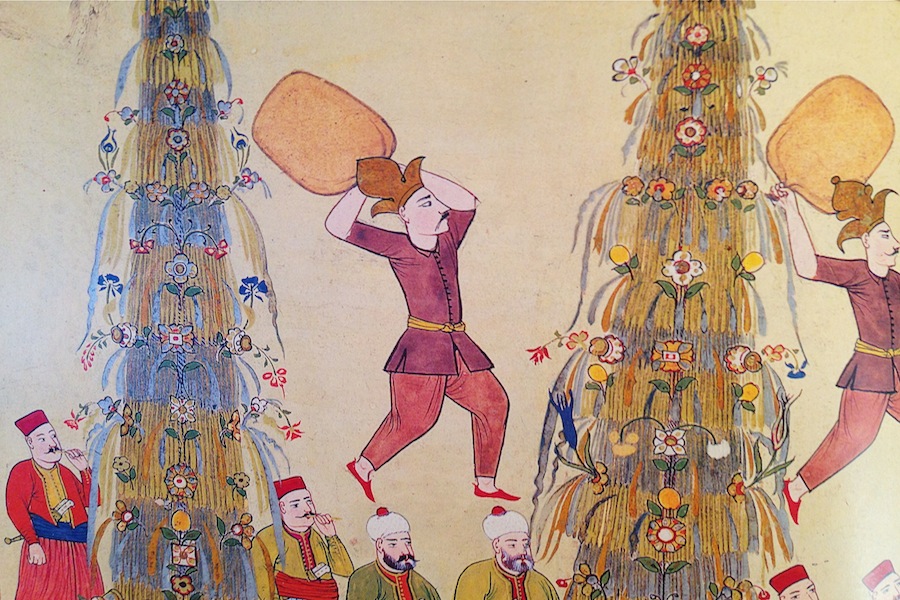

55 Circumcision parade: Nahils and architects are proceeding. Each of them represents one of the princes. Conical structures are decorated with symbols of fruit and flowers.

56 Circumcision parade: Candy gardens are meant to entertain the princes during their recovery period.

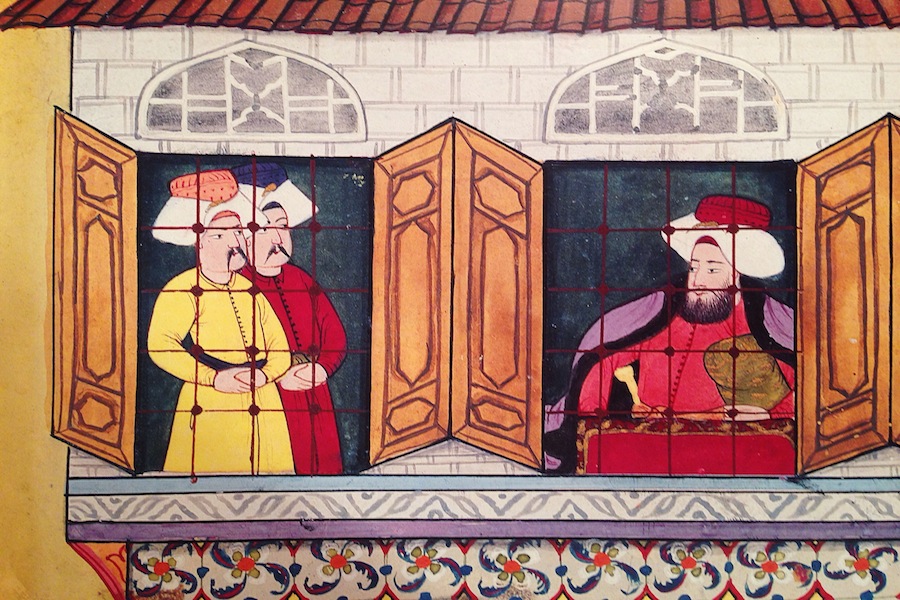

63 Circumcision parade of crown prince Süleyman: Sultan Ahmed III watches the parade from nakkaşhane, the imperial painting studio, which no longer exists. The studio located on Divan Yolu, was adorned with beautiful tiles.

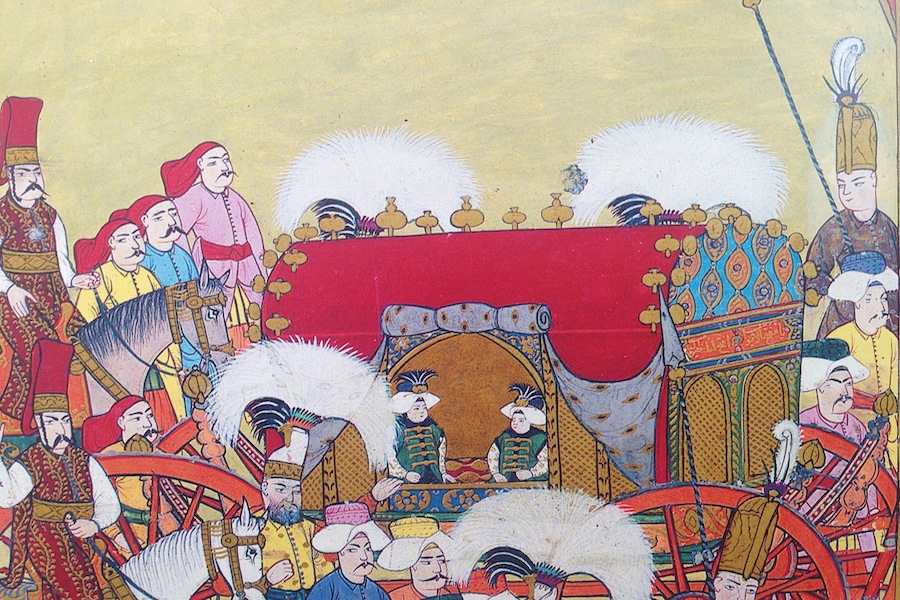

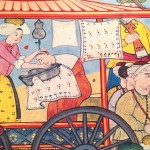

64 Circumcision parade: Prince Mehmed and Mustafa are 3 years of age. They are in a golden carriage drawn by 6 horses.

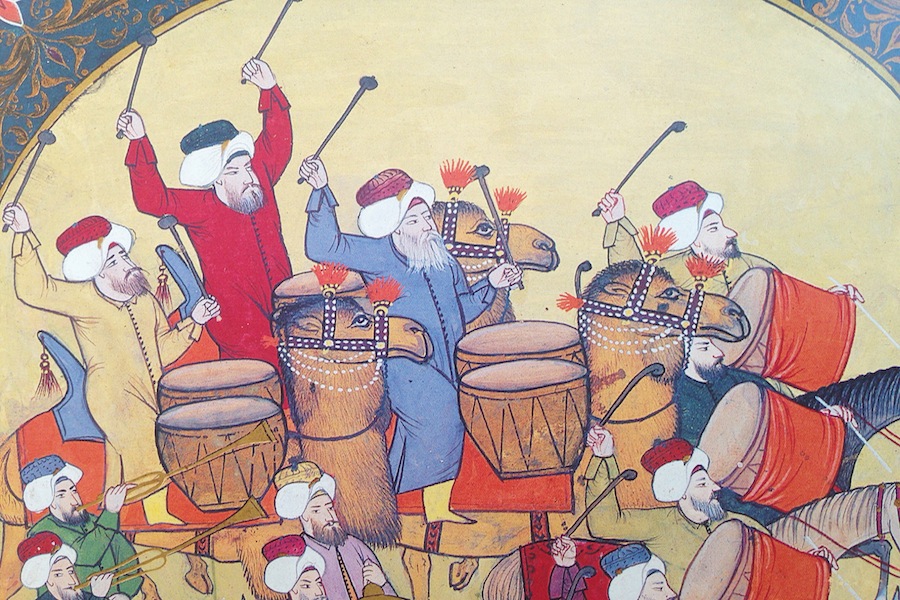

66 Circumcision parade: The mehter, polyphonic military band of the Ottoman army is playing horns, drums, cymbals, and trumpets.

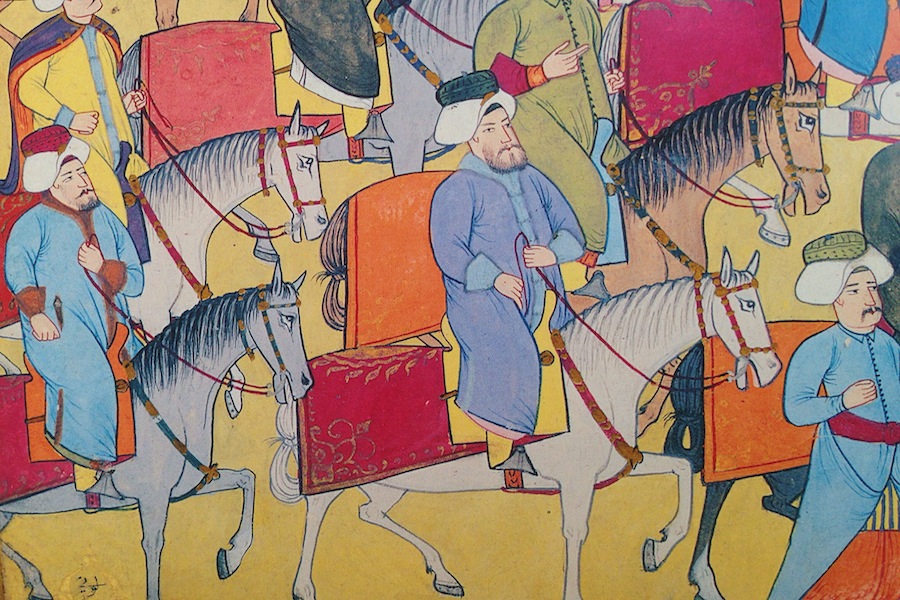

67 Circumcision parade: The procession of the Enderun staff. Because Levni belongs to the Enderun school, he depicted himself as one of the riders and placed his signature below the horse.

68 Ceremonies at the palace: Princes are at the circumcision pavillion on the edge of the big pool, and with the permission of the sultan, the operation starts.

69 The finale: They are resting at the Bagdad pavillion. The operation takes place at the circumcision pavillion. Handfuls of coins are tossed.

Tags: 18th century Aynalıkavak pavillion İlber Ortaylı baroque circumcision Classical Ottoman Age Dimitri Cantemir Esin Atıl festival historiography Koç Publishing House Levni the painter manuscript miniature modernity Okmeydanı ottoman heritage Ottoman identity SALT Galata slide Surname the Book of Festivals tulip tulip period Vehbi the poet

0 Comment